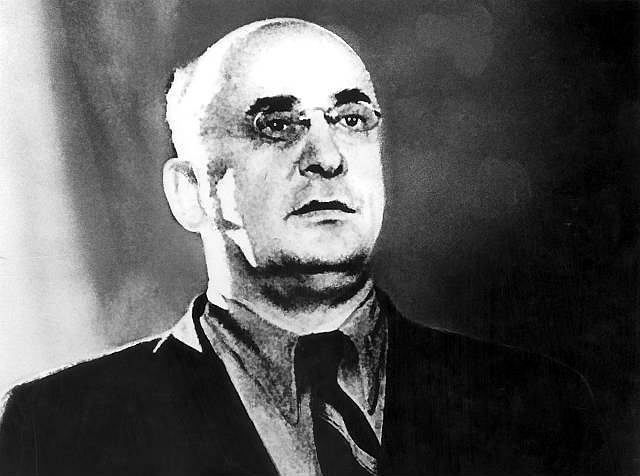

(Following death of Stalin, Beria was the most powerful man in the USSR, but surrounded by enemies on all sides)

On 6 March 1953, the coffin containing Stalin's body was put on display at the Hall of Columns in the House of the Unions, remaining there for three days. On 9 March, the body was delivered to Red Square prior to interment in Lenin's Mausoleum.Speeches were delivered by Khrushchev, Malenkov, Molotov and Beria, after which pallbearers carried the coffin to the mausoleum. As Stalin's body was being interred, a moment of silence was observed nationwide at noon Moscow time. As the bells of the Kremlin Clock chimed the hour, sirens and horns wailed nationwide, along with a 21-gun salute fired from within the precincts of the Kremlin. Similar observances were also held in other Eastern Bloc countries including Mongolia, China and North Korea. Immediately after the silence ended, a military band played the Soviet State Anthem, and then a military parade of the Moscow Garrison was held in Stalin's honor. In their efforts to pay their respects to Stalin, a number of Soviet citizens, many of whom had travelled from across the country to attend the funeral, were crushed and trampled to death in a crowd crush. They were crushed against building walls and Soviet Army trucks, which had been deployed to block off side streets. Mourners, along with mounted police and their horses, were trampled to death in Trubnaya Square. The Soviets did not initially report the event, and the exact number of casualties is unknown. Khrushchev later provided an estimate that 109 people died in the crowd, although the real number of deaths may have been in the thousands.

Stalin's death in March 1953 plunged the Soviet Union into a maelstrom of uncertainty and transition, reshaping the political, economic, social, and international landscape in profound ways. The passing of the long-reigning dictator left the country grappling with a multitude of challenges, both inherited from Stalin's era and emerging in the post-war period. Economically, the Soviet Union faced significant hurdles in the aftermath of World War II. While Stalin's policies of rapid industrialization and collectivization had propelled the country into a position of global prominence, the war had taken a heavy toll on its infrastructure and productive capacity. The industrial heartland, particularly in areas like Ukraine and Belarus, had been ravaged by warfare, leading to widespread destruction and disruption of economic activities. Moreover, the agricultural sector struggled to recover from the upheavals of collectivization. The forced consolidation of farms under Stalin's regime had uprooted traditional farming practices and alienated millions of peasants, leading to resistance and inefficiencies in agricultural production. As a result, food shortages and rationing persisted in the post-war years, exacerbating social tensions and discontent among the populace. Socially, Stalin's legacy cast a long shadow over Soviet society. The pervasive reach of the secret police, epitomized by the infamous NKVD and its successor, the KGB, had instilled a climate of fear and suspicion among the population. The Gulag system, a sprawling network of forced labor camps, held millions of prisoners, many of whom had been swept up in Stalin's purges of the 1930s. The trauma of political repression and state-sponsored violence lingered in the collective memory of the Soviet people, fostering a culture of silence and conformity. Internationally, the Soviet Union found itself locked in a bitter rivalry with the United States and its Western allies as the Cold War intensified. The ideological and geopolitical competition between the two superpowers played out on a global stage, shaping the course of international relations for decades to come. The Soviet Union's efforts to expand its sphere of influence in Eastern Europe and beyond met with resistance and backlash from Western powers, leading to proxy conflicts and diplomatic confrontations around the world.

Following Stalin's demise in March 1953, the Soviet Union entered a pivotal phase marked by significant political shifts, power struggles, and attempts at reform under the leadership of Lavrentiy Beria, Nikita Khrushchev, and Georgy Malenkov. This period, known as the post-Stalin era, witnessed a complex interplay of ideologies, policies, and personalities as the Soviet leadership grappled with the legacy of Stalinism and charted a course for the future of the nation. At the forefront of the post-Stalin leadership was Lavrentiy Beria, a formidable figure with a controversial past as the head of the Soviet security apparatus. Beria's ascent to prominence following Stalin's death was met with both intrigue and apprehension, as his ambitious agenda and political maneuvering set the stage for a dynamic period of transition in Soviet politics. As First Deputy Premier and head of the merged Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) and Ministry of State Security (MGB), Beria wielded considerable influence and sought to implement a series of reforms aimed at liberalizing and restructuring various aspects of Soviet society. One of Beria's key initiatives was the liberalization of the Soviet penal system and the reorganization of the MVD and MGB. By reducing the economic power and penal responsibilities of these agencies, Beria aimed to curtail the excesses of Stalin's regime and alleviate the burden on the Soviet populace. He oversaw the closure of costly construction projects and the restructuring of industrial enterprises, signaling a shift away from Stalinist economic policies and towards greater efficiency and rationalization in resource allocation. Beria's liberalization efforts extended beyond the economic sphere to address issues of nationalities and cultural identity within the Soviet Union. As a Georgian himself, Beria questioned the policy of Russification and advocated for greater autonomy for non-Russian republics. In Georgia, he halted Stalin's fabricated Mingrelian affair and promoted the appointment of pro-Beria Georgians to key positions, signaling a departure from the centralized control exerted by Moscow and a recognition of local identities and aspirations. Furthermore, Beria's foreign policy initiatives aimed to restore relations with estranged allies such as Titoist Yugoslavia and to critique Soviet interventions in Eastern Europe. He advocated for a more conciliatory approach towards Eastern Bloc countries and proposed abandoning the heavy-handed tactics employed by Stalin in favor of diplomatic engagement and cooperation. Beria's vision for a united, neutral Germany reflected his desire to defuse tensions and promote stability in post-war Europe, echoing Stalin's earlier proposals for détente with the Western powers.

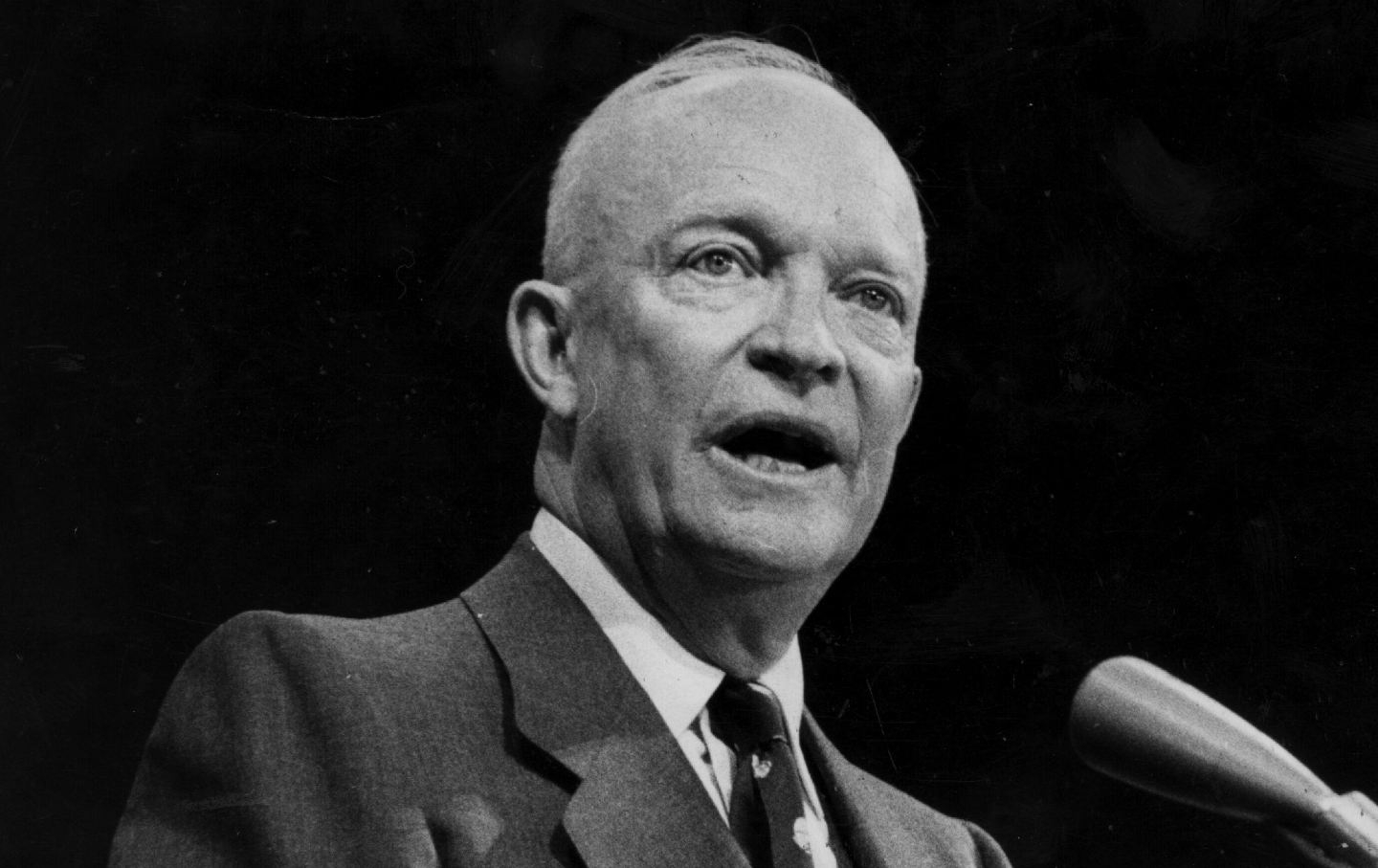

(President Eisenhower delivering Chance for Peace speech)

The Chance for Peace speech, also known as the Cross of Iron speech, was an address given by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower on April 16, 1953, shortly after the death of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Speaking only three months into his presidency, Eisenhower likened arms spending to stealing from the people, and evoked William Jennings Bryan in describing "humanity hanging from a cross of iron." Eisenhower took office in January 1953, with the Korean War in a stalemate. Three and a half years prior, the Soviet Union had successfully detonated the atomic bomb named RDS-1, and appeared to reach approximate military parity with the United States. Political pressures for a more aggressive stance toward the Soviet Union mounted, and calls for increased military spending did as well. Stalin's demise on March 5, 1953, briefly left a power vacuum in the Soviet Union and offered a chance for rapprochement with the new Soviet government as well as an opportunity to decrease military spending. The speech was addressed to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, in Washington D.C., on April 16, 1953. Eisenhower took an opportunity to highlight the cost of continued tensions and rivalry with the Soviet Union. While addressed to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, the speech was broadcast nationwide, through use of television and radio, from the Statler Hotel. He noted that not only were there military dangers (as had been demonstrated by the Korean War), but an arms race would place a huge domestic burden on both nations:

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. The cost of one modern heavy bomber is this: a modern brick school in more than 30 cities. It is two electric power plants, each serving a town of 60,000 population. It is two fine, fully equipped hospitals. It is some fifty miles of concrete pavement. We pay for a single fighter with a half-million bushels of wheat. We pay for a single destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than 8,000 people. . . . This is not a way of life at all, in any true sense. Under the cloud of threatening war, it is humanity hanging from a cross of iron.

Following Stalin's death in March 1953, Lavrentiy Beria's rise to power and his subsequent attempts to consolidate control over the Soviet Union were met with growing opposition from within the highest echelons of the Communist Party. As First Deputy Premier and head of the merged Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) and Ministry of State Security (MGB), Beria wielded significant influence and sought to implement a series of reforms aimed at liberalizing and restructuring Soviet society. However, his ambitious agenda and authoritarian methods quickly alienated key members of the Politburo, including Nikita Khrushchev and his allies. Beria's aggressive tactics and disregard for party protocol fueled resentment and suspicion among his colleagues, leading to a climate of mutual mistrust and hostility within the Politburo. Khrushchev, in particular, emerged as a vocal critic of Beria's rule, viewing him as a threat to his own ambitions and the stability of the Soviet system. Alongside his allies in the party leadership, Khrushchev embarked on a campaign to stonewall Beria at every opportunity, thwarting his initiatives and undermining his authority at every turn. The growing opposition to Beria's rule was fueled by a combination of ideological differences, personal animosities, and fears of authoritarianism. Beria's past as the head of the Soviet security apparatus and his involvement in Stalin's repressive regime cast a shadow over his leadership, raising concerns about his commitment to party principles and democratic norms. Khrushchev and his allies viewed Beria's attempts to centralize power and suppress dissent with suspicion, fearing a return to the repressive tactics of the Stalin era.

Beria's confrontational style and disregard for party consensus further alienated him from his colleagues, exacerbating tensions within the Politburo and fueling the mutual animosity between Beria and the rest of the leadership. As Beria sought to assert his authority and implement his agenda, Khrushchev and his allies worked tirelessly to block his initiatives and weaken his position within the party hierarchy. This power struggle played out behind the scenes, with clandestine meetings, backroom negotiations, and strategic alliances shaping the dynamics of Soviet politics in the post-Stalin era. Amidst the growing opposition to Beria's rule, tensions reached a boiling point within the Politburo, culminating in a series of confrontations and power struggles that threatened to destabilize the Soviet state. Beria's attempts to consolidate power and silence his critics only fueled resistance and fueled rumors of dissent and conspiracy within the party ranks. As Khrushchev and his allies rallied support against Beria's leadership, the stage was set for a dramatic showdown that would shape the course of Soviet politics in the months to come. In the tumultuous period between March and April 1953, the struggle for power and influence within the Soviet leadership intensified, with Beria's opponents gaining momentum and mobilizing against his rule. As the mutual animosity between Beria and the rest of the Politburo reached new heights, the fate of the Soviet Union hung in the balance, with the outcome of the power struggle poised to determine the future direction of the nation.

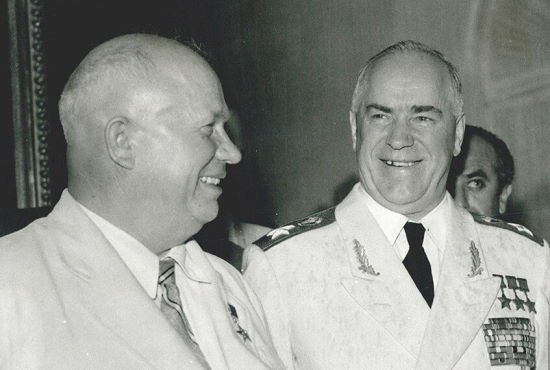

(Khruschev and Zhukov knew that they must act fast before Beria consolidated his power completely)

In the tense political climate of post-Stalin Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev's growing concern about Lavrentiy Beria's rising influence led him to seek an alliance with Marshal Georgy Zhukov, a highly respected figure within the Red Army and a veteran commander of World War II. Khrushchev recognized Zhukov's pivotal role in the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany and valued his strategic insight and leadership qualities. Their meeting to discuss the growing threat posed by Beria marked a crucial turning point in the power struggle within the Soviet leadership. As they convened to discuss the situation, Zhukov's memories of Beria's role in the Great Purge and the subsequent decimation of the officer corps in the late 1930s were still fresh. Zhukov, having witnessed firsthand the devastating impact of Beria's actions on the military ranks, harbored deep-seated resentment towards the former head of the security apparatus. He understood the dangers posed by Beria's unchecked ambition and authoritarian tendencies, recognizing the need to prevent history from repeating itself. Khrushchev, too, shared Zhukov's concerns about Beria's ascent to power. Aware of Beria's ruthless tactics and his willingness to eliminate perceived threats to his authority, Khrushchev saw the urgent need to neutralize Beria's influence before it posed a greater threat to the stability of the Soviet Union. Recognizing Zhukov's stature and credibility within the military establishment, Khrushchev sought to leverage their alliance to rally support against Beria's leadership. During their meeting, Khrushchev and Zhukov agreed that Beria must be stopped at all costs to safeguard the integrity of the Soviet state and prevent a return to the repressive tactics of the Stalin era. They recognized the importance of decisive action and strategic collaboration in confronting the growing threat posed by Beria's authoritarian rule. Drawing upon their respective strengths and spheres of influence, they devised a plan to undermine Beria's authority and rally support for his removal from power. Their alliance marked a significant turning point in the power struggle within the Soviet leadership, as Khrushchev and Zhukov joined forces to confront a common enemy and defend the principles of party unity and collective leadership. Their determination to thwart Beria's ambitions reflected a broader consensus among key members of the Politburo, who recognized the need to prevent any one individual from monopolizing power and undermining the democratic principles of the Soviet system.

As they embarked on their campaign to neutralize Beria's influence, Khrushchev and Zhukov faced formidable challenges and formidable adversaries. Beria's loyalists and allies within the party apparatus posed a formidable obstacle to their plans, and the stakes of their struggle for power were nothing less than the future direction of the Soviet Union. Yet, driven by a shared commitment to the principles of party unity and collective leadership, Khrushchev and Zhukov forged ahead with their alliance, determined to confront the growing threat posed by Beria and safeguard the integrity of the Soviet state. As Nikita Khrushchev and Marshal Georgy Zhukov strategized their efforts to counter Lavrentiy Beria's growing influence, Beria himself was not idle. Recognizing the mounting opposition within the Politburo, the Communist Party, and the Red Army, Beria embarked on a covert campaign to consolidate his power and eliminate his adversaries once and for all. Beria, drawing upon his extensive network of loyalists and operatives within the state security apparatus, initiated a meticulously planned plot to execute a preemptive strike against his opponents. Utilizing his control over the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) and the Ministry of State Security (MGB), Beria orchestrated a series of clandestine operations aimed at neutralizing key figures perceived as threats to his authority. Under Beria's orders, loyal agents within the security services were mobilized to identify and surveil individuals deemed disloyal or opposed to his leadership. Using sophisticated surveillance techniques and covert surveillance methods, Beria's operatives monitored the activities and communications of targeted individuals, gathering intelligence on their movements, affiliations, and factional allegiances.

(Beria's gamble to get rid of all political enemies turned out to be his last)

On fateful 28 April 1953, Lavrentiy Beria orchestrated a meticulously planned coup within the highest echelons of Soviet power, aiming to solidify his own authority and eliminate any potential threats to his rule. As the members of the Politburo gathered for what they believed would be a routine meeting, little did they know that they were about to become pawns in Beria's ruthless game of political maneuvering. Beria's opening salvo was a scathing diatribe against his fellow Politburo members, accusing them of treachery and disloyalty to the Soviet cause. With each accusation, he sought to tarnish the reputations of his rivals and cast doubt on their commitment to socialism and the principles of the Communist Party. Drawing upon a carefully crafted narrative of deception and betrayal, Beria presented his colleagues as agents of counter-revolutionary forces, intent on undermining the foundations of the Soviet state. Utilizing fabricated evidence and trumped-up charges, he painted a chilling picture of a conspiracy aimed at destabilizing the Soviet Union and toppling its leadership. Before his stunned audience could fully grasp the gravity of the situation, Beria unleashed his secret weapon: a cadre of loyal operatives from the feared MGB and MVD, armed to the teeth and ready to enforce his will. With military precision, they stormed into the meeting room, their faces masked and their intentions clear. Amidst the chaos and confusion, the members of the Politburo found themselves surrounded by armed agents, their protests drowned out by the din of shouting voices and the harsh commands of their captors. In a matter of moments, they were forcibly detained and whisked away to face an uncertain fate, their once-secure positions of power now hanging in the balance. For Beria, the swift and decisive action was a calculated gamble, designed to eliminate any opposition to his rule and consolidate his grip on the reins of power. With his rivals neutralized and their voices silenced, he stood poised to reshape the course of Soviet history according to his own ambitions and desires.

Simultaneously with the dramatic events unfolding within the confines of the Politburo meeting, units of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) and the Ministry of State Security (MGB) loyal to Lavrentiy Beria sprang into action to secure critical points throughout Moscow. In a meticulously coordinated operation, these units moved swiftly and decisively to assert control over key strategic locations, ensuring that Beria's grip on power would remain unchallenged. Armed with orders directly from Beria himself, these loyalist forces fanned out across the city, their presence serving as a visible reminder of his authority and determination to quash any opposition. From government buildings to military installations, from transportation hubs to communication centers, no location deemed essential to maintaining order and enforcing Beria's will was left unguarded. At government ministries and party headquarters, MVD and MGB agents took up positions to prevent any attempts at resistance or counteraction from rival factions within the bureaucracy. With their superior firepower and unwavering loyalty to Beria, these units stood ready to neutralize any threats to him and ensure that the transition of power would proceed smoothly according to Beria's plan. Meanwhile, at key transportation nodes such as railway stations and airports, MVD forces established checkpoints and conducted rigorous inspections to monitor the movement of individuals in and out of the city. Their goal was to prevent any potential adversaries from escaping or seeking refuge outside of Moscow, thus containing the threat posed by dissenting elements and tightening control over the capital. In addition, communication centers and media outlets came under the watchful eye of MGB operatives, who closely monitored all forms of information dissemination to prevent the spread of dissent or opposition propaganda. By controlling the flow of information and suppressing any dissenting voices, Beria sought to maintain a tight grip on the narrative and ensure that its version of events would prevail unchallenged.

(Marshall Zhukov's beforehand preparations saved the Politburo and the USSR from Beria)

Despite Lavrentiy Beria's meticulous planning and the swift mobilization of loyal MVD and MGB units across Moscow, his attempt to seize control of the Soviet state faced a formidable obstacle in the form of Marshal Georgy Zhukov, who had anticipated such a move and prepared his own counterplan to thwart Beria's ambitions. Zhukov, a seasoned military strategist and revered hero of the Great Patriotic War, had long been wary of Beria's machinations and had taken precautions to safeguard the integrity of the Soviet Union against any internal threats. As Beria's forces moved to secure critical points in Moscow, Zhukov activated his own network of loyalists within the Red Army and implemented a carefully coordinated response to neutralize Beria's coup attempt. With lightning speed, Zhukov deployed Red Army forces to strategic positions throughout Moscow, establishing checkpoints and defensive perimeters to isolate Beria and his loyalists within the city while cutting off communication and transportation links to the rest of the USSR. Troops loyal to Zhukov fanned out across the capital, securing key infrastructure and government buildings to prevent any further incursions by Beria's forces. At the same time, Zhukov issued orders to his commanders across the country, mobilizing additional military units and reinforcing border defenses to ensure that Beria would not be able to extend his influence beyond Moscow's borders. With the Red Army firmly under his command, Zhukov acted decisively to contain the threat posed by Beria's coup attempt and maintain the stability of the Soviet state. Zhukov's swift and decisive response caught Beria off guard, effectively thwarting his plans for a power grab and ensuring that the Soviet Union remained united under the leadership of the Red Army. By isolating Beria within Moscow and cutting off communication with the rest of the country, Zhukov effectively neutralized the threat posed by Beria's faction and preserved the integrity of the Soviet state during this critical moment of crisis.

As the tense standoff between Lavrentiy Beria and Marshal Georgy Zhukov unfolded over the course of three harrowing hours, both sides engaged in a high-stakes game of brinkmanship, each determined to emerge victorious and assert their authority over the fate of the Soviet Union. Cut off from the rest of the country by Zhukov's strategic maneuvers, Beria found himself in a precarious position, his grip on power slipping as Zhukov's forces tightened their grip on Moscow. Aware of the gravity of the situation and desperate to regain the upper hand, Beria resorted to increasingly desperate measures to coerce Zhukov into standing down. With the fate of the Politburo hanging in the balance, Beria issued a chilling ultimatum, threatening to execute the imprisoned members of the Politburo unless Zhukov capitulated to his demands. The threat of violence loomed large as Beria's forces prepared to carry out his grim warning, their weapons trained on the terrified Politburo members who were held captive within the confines of their makeshift prison. Zhukov, undeterred by Beria's brazen intimidation tactics, stood firm in his resolve, refusing to yield to Beria's demands and steadfastly maintaining his position as the defender of the Soviet state. As the standoff entered its critical phase, tensions reached a fever pitch, with both Beria and Zhukov fully aware that the fate of the Soviet Union hung in the balance. With the clock ticking and the specter of bloodshed looming large, the fate of millions rested on the outcome of this epic struggle for power and supremacy within the highest echelons of the Soviet hierarchy. For three agonizing hours, the fate of the Soviet Union teetered on the brink of catastrophe as Beria and Zhukov engaged in a deadly game of cat and mouse, each determined to outmaneuver the other and emerge victorious in this epic battle for control. As the sun set over the besieged city of Moscow, the outcome of this fateful confrontation remained uncertain, with the future of the Soviet Union hanging in the balance.

As Lavrentiy Beria's forces launched their breakout attempt in defiance of Marshal Georgy Zhukov's steadfast resistance, the streets of Moscow erupted into chaos as the Battle of Moscow unfolded with ferocious intensity. The clash between the MVD and MGB troops loyal to Beria and the Red Army forces under Zhukov's command marked a pivotal moment in the struggle for supremacy within the Soviet capital, unleashing a wave of violence and bloodshed that would leave a lasting scar on the city. From the early hours of the morning until the fading light of dusk, the sounds of gunfire and explosions echoed through the streets of Moscow as opposing forces waged a bitter struggle for control of the city. Armed with rifles, machine guns, and grenades, Beria's troops fought desperately to break through Zhukov's defensive lines, while the Red Army units, bolstered by their unwavering loyalty to Zhukov and the Soviet state, stood firm in their determination to repel the assault and maintain order. Amidst the smoke and chaos of battle, the city became a battleground, with key strategic points such as government buildings, military installations, and transportation hubs hotly contested by both sides. Buildings were reduced to rubble, streets ran red with blood, and the air was thick with the acrid scent of gunpowder as the opposing forces clashed in a brutal struggle for supremacy

. The Battle of Moscow raged on relentlessly throughout the day, exacting a heavy toll on both sides as casualties mounted and the death toll soared. In the heat of battle, acts of heroism and sacrifice were witnessed on both sides, as soldiers and civilians alike bravely fought to defend their city and their ideals against the onslaught of violence and tyranny. As night fell and the smoke cleared, the true cost of the day's carnage became painfully apparent. An estimated 2,500 people lay dead, their lives sacrificed in the name of power and ambition. The scars of the Battle of Moscow would linger long after the last shots had been fired, serving as a grim reminder of the fragility of peace and the depths of human conflict. As the sun set on the blood-stained streets of Moscow, the Red Army emerged victorious in the Battle of Moscow, decisively defeating the forces of the MVD and MGB loyal to Lavrentiy Beria. The echoes of gunfire faded into the night, replaced by an eerie silence that hung over the city like a shroud as the dust settled on the battlefield.

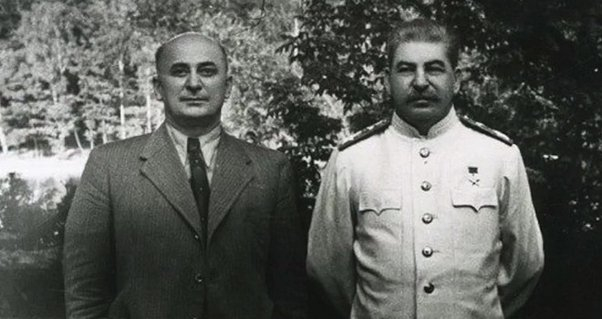

(Just within 2 months two most powerful man in the Soviet system were no more)

In the aftermath of the brutal conflict, the MVD and MGB agents who had held the Politburo captive during Beria's ill-fated coup found themselves facing a stark choice: remain loyal to their fallen leader and face certain defeat, or betray Beria in a desperate bid to save their own lives. Faced with the prospect of retribution from the victorious Red Army and the wrath of the Politburo members they had betrayed, many of Beria's erstwhile supporters chose the path of self-preservation, turning on their former master in a bid to secure their own survival. With the balance of power shifting decisively against him, Beria found himself abandoned and isolated, betrayed by those he had trusted most. As the Red Army closed in on his position, Beria's once-vaunted authority crumbled, his grand ambitions reduced to ashes in the wake of his spectacular defeat.

In a dramatic turn of events, the MVD and MGB agents who had held the Politburo captive turned on Beria, arresting him and delivering him into the hands of the victorious Red Army. With their former oppressor now in custody, the agents sought to curry favor with the newly triumphant authorities, hoping to secure leniency for their own roles in Beria's failed coup. Meanwhile, the Politburo members who had been held captive by Beria's forces were released from their confinement, their ordeal at an end. Emerging from captivity, they found themselves thrust back into the heart of the political maelstrom, determined to restore order and stability to the Soviet Union in the wake of Beria's downfall. As dawn broke over Moscow, the city awakened to a new reality, one shaped by the tumultuous events of the previous day. With Beria's coup thwarted and his reign of terror brought to an ignominious end, the Soviet Union stood at a crossroads, poised to chart a new course forward under the leadership of those who had emerged victorious in the struggle for power. Yet, even as the dust settled on the battlefield, the scars of the Battle of Moscow served as a stark reminder of the fragility of power and the ever-present specter of conflict that loomed over the nation's future.

With the apprehension of Lavrentiy Beria, Marshal Zhukov and the Red Army swiftly moved to restore order in Moscow, quelling the chaos and uncertainty that had gripped the city in the wake of Beria's failed coup attempt. Troops were deployed throughout the capital, patrolling the streets and maintaining a vigilant watch to ensure that no remnants of Beria's loyalists could threaten the newfound stability. As news of Beria's arrest spread like wildfire throughout Moscow, a palpable sense of relief swept over the city, tempered by lingering anxiety over the specter of further unrest. Yet, amidst the turmoil, a collective sense of gratitude emerged for the swift and decisive action taken by Marshal Zhukov and the Red Army in thwarting the treacherous plot orchestrated by Beria and his cohorts. In a series of public announcements and broadcasts, Zhukov and his fellow military commanders wasted no time in sharing the news of Beria's downfall with the populace, casting the coup attempt as a desperate act of treachery orchestrated by a foreign agent bent on undermining the Soviet Union from within. Through a carefully crafted narrative, Zhukov sought to portray the Red Army as the stalwart defenders of the motherland, bravely standing firm against the machinations of external foes and internal traitors alike. With each proclamation and declaration, Zhukov reinforced the image of the Red Army as the vanguard of Soviet strength and resilience, instilling a sense of pride and unity among the citizenry in the face of adversity. In the aftermath of Beria's arrest, the streets of Moscow resounded with chants of "Long live the Red Army!" and "Death to traitors!" as ordinary citizens hailed the bravery and valor of their military defenders.

Amidst the jubilant celebrations, Zhukov and his fellow leaders worked tirelessly to consolidate their grip on power, rooting out any remaining pockets of resistance and reaffirming their authority over the city. Through a combination of military might and strategic diplomacy, they sought to reassure the populace that the Soviet Union remained steadfast and unwavering in the face of external threats and internal strife. As the dust settled on the tumultuous events of the previous days, Moscow gradually returned to a semblance of normalcy, albeit forever changed by the seismic shifts in power and the specter of betrayal that had gripped the city. Yet, amidst the lingering echoes of gunfire and the fading memories of chaos, one truth remained clear: the Red Army had prevailed, and the Soviet Union stood strong, united, and resolute in the face of adversity.

After being apprehended and brought to the bunker of the headquarters of the Moscow Military District, Lavrentiy Beria and his cohorts faced the grim specter of justice in the wake of their failed coup attempt. The proceedings that followed were a stark reminder of the ruthlessness of Soviet power and the unforgiving nature of the Soviet system they had once served. Beria's trial by a "special session" of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union on April 29, 1953, was a chilling display of the state's authority, devoid of any semblance of due process or fairness. Led by Marshal Ivan Konev, a figure of formidable stature within the Soviet hierarchy, the tribunal served as a grim theater of justice, where the fate of the accused was sealed before the first gavel fell. With no defense counsel to plead their case and no avenue for appeal, Beria and his associates stood alone against the full force of the state. The charges brought against them—treason, terrorism, counter-revolutionary activity—were grave indeed, reflecting the magnitude of their transgressions against the Soviet order.

As the trial unfolded, the atmosphere in the bunker was thick with tension and anticipation. Beria, once a figure of immense power and influence, now found himself at the mercy of a system he had once manipulated with impunity. His pleas for clemency fell on deaf ears, drowned out by the weight of evidence and the clamor of the court. In a moment of desperation, Beria allegedly fell to his knees, a stark symbol of his downfall and a testament to the fleeting nature of power. His cries for mercy echoed through the chamber, a haunting reminder of the hubris that had led him to this moment of reckoning. With the verdict pronounced and the sentence delivered, Beria and his fellow defendants faced the ultimate penalty: death. The executioner's bullet, swift and merciless, brought an end to their lives and their reign of terror, extinguishing the flames of their ambition in a blaze of violence. Beria's final moments, as he stared into the abyss of his own mortality, bore a haunting resemblance to those of his predecessors—men who had met similar fates at the hands of the Soviet state. His death, like theirs, was a grim reminder of the price of power and the dangers of unchecked ambition. In death, Beria's legacy lived on—a legacy of tyranny, terror, and ultimately, ignominious demise. His body, cremated and cast into the waters of the Moscow River, served as a grim testament to the transient nature of power and the inexorable march of history.

(Now the fate of the USSR and Soviet people was in hands of Marshall Zhukov and the new Soviet government)

Following the tumultuous events surrounding Beria's coup attempt and subsequent demise, the Soviet Union found itself at a critical juncture, with the balance of power hanging in the balance. Marshal Zhukov, hailed once again as the savior of the nation, emerged as a towering figure on the political landscape, his reputation as a military hero now matched by his role in thwarting Beria's ambitions. As the dust settled and the repercussions of the coup attempt reverberated throughout the corridors of power, a sense of unease gripped the highest echelons of the Soviet leadership. Nikita Khrushchev, whose failed attempt to anticipate Beria's machinations had nearly cost the lives of the entire Politburo, found himself isolated and vulnerable, his aspirations for leadership dashed by his own miscalculations. In the wake of these events, the Politburo convened to chart a new course for the Soviet Union, with Anastas Mikoyan emerging as a key figure in shaping the debate. Recognizing Zhukov's indispensable role in preserving the integrity of the state, Mikoyan proposed a bold solution: that Zhukov should assume leadership of the USSR, ushering in a new era of stability and progress under his stewardship. The suggestion garnered widespread support among the Politburo members, many of whom were eager to align themselves with Zhukov's aura of invincibility and capitalize on his newfound popularity among the masses. However, concerns lingered about the potential implications of a military figure assuming the highest office in the land, with fears of a perceived takeover by the Red Army casting a shadow over the deliberations. To address these apprehensions, it was agreed that Zhukov would transition from his military role to a civilian one, assuming the position of First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. This move, while ensuring that Zhukov's leadership remained firmly rooted in the political sphere, also served to assuage concerns about the militarization of the state and preserve the delicate balance of power between the party and the armed forces.

With Zhukov's ascent to the position of First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, a new era dawned for the Soviet Union, marked by a renewed sense of stability and purpose. As the nation sought to navigate the aftermath of Beria's failed coup and chart a course for the future, Zhukov's leadership promised to steer the country toward calmer waters.

Anastas Mikoyan, a seasoned statesman with a reputation for pragmatism and diplomacy, was tapped to assume the role of premier, entrusted with the formidable task of overseeing the day-to-day governance of the Soviet Union. Mikoyan's appointment was met with approval from within the party ranks, as his steady hand and political acumen were seen as essential assets in the post-coup landscape. Meanwhile,

Nikita Khrushchev, chastened by his near brush with disaster and cognizant of his own limitations, accepted the position of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Though relegated to a more ceremonial role as the titular head of state, Khrushchev remained a prominent figure within the Soviet hierarchy, his experience and influence still wielded with caution and respect. As the new leadership structure took shape, the Soviet Union embarked on a period of consolidation and introspection, seeking to address the underlying grievances and challenges that had precipitated the turmoil of recent years. Under Zhukov's firm but measured guidance, the party sought to reaffirm its commitment to socialist ideals while embracing pragmatic reforms aimed at modernizing the economy and improving the standard of living for all citizens. Mikoyan, for his part, set about implementing a series of administrative reforms designed to streamline government operations and promote greater efficiency in decision-making. His emphasis on consensus-building and consultation fostered a spirit of cooperation within the leadership ranks, laying the groundwork for a more cohesive and effective governance structure. Meanwhile, Khrushchev, despite his diminished role, remained a vocal advocate for social and economic reforms, using his position to champion causes dear to his heart, such as agricultural modernization and de-Stalinization. Though no longer at the pinnacle of power, Khrushchev's influence continued to be felt within the party apparatus, as his populist appeal resonated with broad segments of the Soviet populace. As the Soviet Union embarked on this new chapter in its history, the specter of Beria's failed coup served as a cautionary tale, a stark reminder of the fragility of power and the dangers of unchecked ambition. Yet, with Zhukov at the helm, supported by Mikoyan and Khrushchev, the Soviet Union stood poised to confront the challenges of the future with renewed vigor and determination.

In the aftermath of Lavrentiy Beria's failed coup and the ascension of Marshal Zhukov as the new First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the Western world watched with a mixture of apprehension and cautious optimism. The sudden upheaval within the Soviet leadership sent ripples across the global stage, prompting leaders in the West to reassess their strategies and policies toward the Soviet Union. For many Western governments, Zhukov's emergence as the de facto leader of the USSR marked a significant shift in the geopolitical landscape. As a revered military figure who played a pivotal role in the defeat of Nazi Germany during World War II, Zhukov commanded respect and admiration both at home and abroad. His reputation as a pragmatic and decisive leader offered hope for a more stable and predictable Soviet Union, potentially opening the door to improved diplomatic relations and reduced tensions between East and West. At the same time, however, Western leaders remained wary of Zhukov's background as a career military officer, fearing that his leadership could signal a more assertive and militaristic approach to Soviet foreign policy. Memories of the Cold War and the looming specter of nuclear conflict cast a shadow over any prospects for détente, as Western governments grappled with the challenge of navigating the complexities of superpower rivalry in an era of heightened geopolitical competition. In Washington, policymakers in the United States viewed Zhukov's rise to power through the prism of national security and strategic interests. While some saw the potential for a more pragmatic and rational interlocutor in the Kremlin, others remained skeptical of Soviet intentions and wary of any signs of weakness or instability within the Soviet leadership. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and other intelligence agencies closely monitored developments in Moscow, analyzing Zhukov's statements and actions for clues to his intentions and priorities.

In Western Europe, leaders grappled with similar concerns about the implications of Zhukov's leadership for regional security and stability. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) bolstered its defenses along the Iron Curtain, wary of any potential Soviet moves to exploit perceived vulnerabilities in the wake of Beria's failed coup. At the same time, European leaders expressed cautious optimism about the prospects for renewed dialogue and engagement with Moscow, recognizing the importance of maintaining open channels of communication and diplomacy. In the media and public discourse, Zhukov's ascent to power sparked lively debate and speculation about the future trajectory of Soviet-Western relations. Analysts and commentators offered a range of perspectives on the implications of Zhukov's leadership for global geopolitics, with some predicting a thaw in tensions and others warning of the continued risk of confrontation and conflict. The reaction from the West to Beria's failed coup and Zhukov's rise to power reflected a mix of hope, skepticism, and uncertainty. As the world awaited further developments in Moscow, the stage was set for a new chapter in the ongoing saga of the Cold War, with the fate of East-West relations hanging in the balance.